OUR HISTORY

The following is an excerpt from Dr Jim Lewis’ fascinating history of the Lea Valley: Britain's Best Kept Secret (1999).

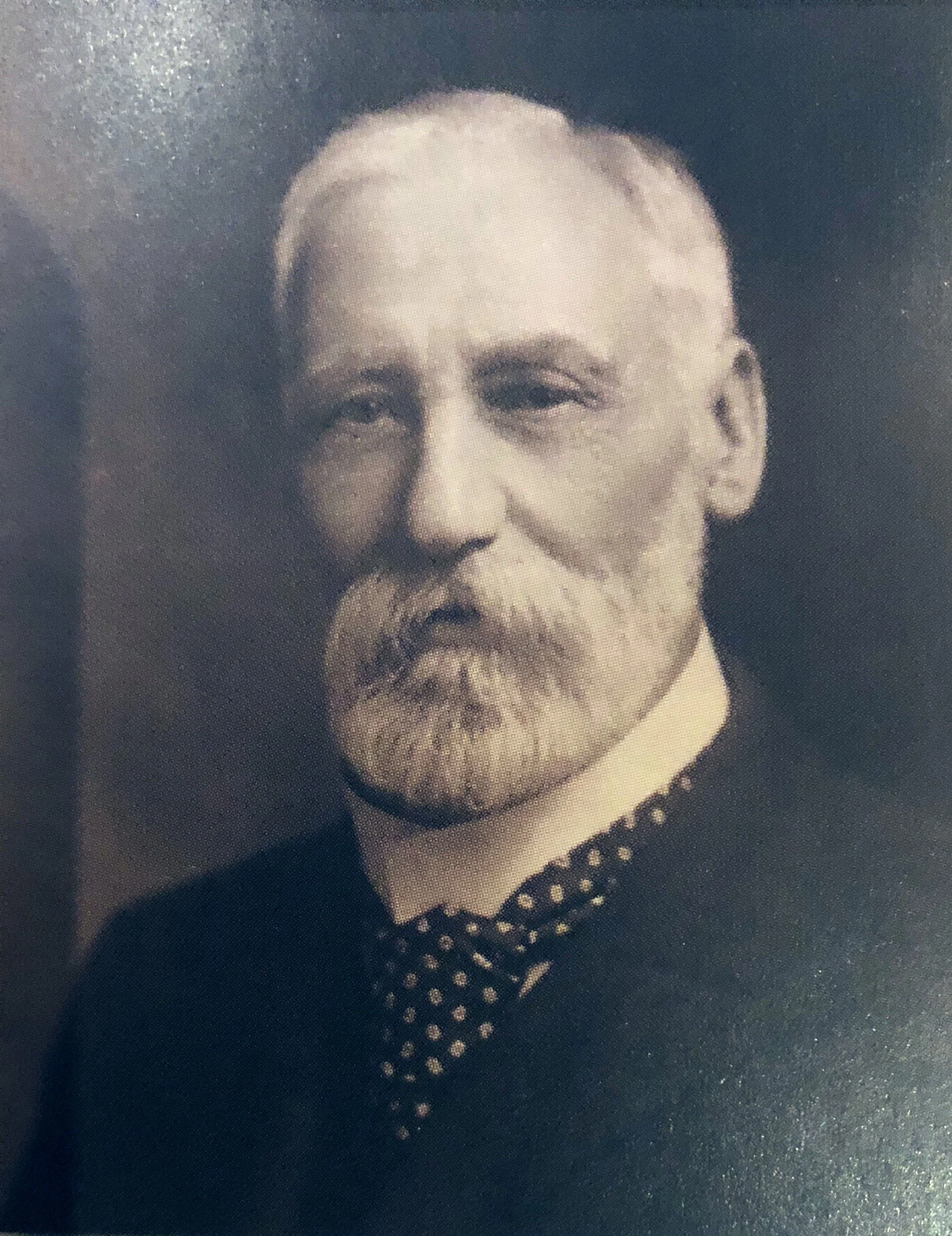

In 1867 George Reynolds Wright came to Enfield and entered into partnership with James Dilly Young, the miller of Ponders End Mill, taking up residence in the East Mill House. The house, built in the reign of Queen Anne, is in active use today providing the necessary accommodation to administer the only independent family run flour mill in London. Speaking to directors and staff of this company will immediately reveal a love and enthusiasm for a proud tradition of milling at Ponders End, whose roots can be traced back as far as Domesday Book.

By the early years of the 17th century the mill was known as Flanders Mill. Power to drive the seven pairs of millstones came from the River Lea via two breast water wheels. Evidence of this earlier waterpower can still be observed today. If a visitor stands on the bridge, which is part of the Lea Valley Road running between the King George and William Girling reservoirs, and looks north, a weir will be seen which allows water from the river to enter the mill head stream that passes directly below them. In the 18th century the mill became known as Enfield Mill, changing its name again halfway through the 19th century to Ponders End Mill.

In the early days of milling, flour had to be delivered to the bakeries of London and the surrounding area by horse-drawn wagon. A typical day for the carman would start around 6a.m. when he would leave the mill with a full load of five tons, ensuring the route he took did not have too many steep and difficult slopes. After a round trip of some ten to twenty miles he would return about 7p.m., not finishing the day until his main asset, the horses, had been fed, watered and stabled. Next day, an appointed operative would come to work early in the morning to see that the horses were harnessed and ready for the day's deliveries.

By 1909 the new technology of electricity had become the energy source and traditional methods of powering the mill-water and steam-were abandoned. This also gave the opportunity to replace the ageing millstones, which required regular maintenance and dressing by skilled craftsmen, with modern efficient roller machinery which, at the time, was being introduced almost universally by the milling industry. However, up until the 1960s some of the millstones were retained by Wright's, who were committed to maintaining a service to a number of their customers who required specialist flour.

The early 20th century also brought with it an improved road network and in August 1906 the Company took advantage of this by acquiring a steam wagon. This dramatically increased the amount of flour which could be transported compared with the horse-drawn wagon. However, steam wagons of the day had certain drawbacks. Initially these vehicles had solid iron wheels which caused considerable problems for their drivers when descending or ascending hills with bulk loads of between fifteen and twenty tons, particularly when the roads were icy or wet. Those were hard times for our ancestors but we can be proud of their achievements which have helped successive generations of Wrights to invest confidently in the future of the mill, preserving part of the Lea Valley's rich industrial heritage

The year 1938 saw a significant leap forward in the fortunes of the mill when the directors, no doubt with expansion firmly in mind, purchased, from the Metropolitan Water Board, freehold ownership of a little over eleven acres of surrounding land and the entitlement of passage for barges from and to the Lee Navigation.

When the Second World War commenced in 1939 the mill came under Government control. To help secure food supplies for the nation, and to supplement the losses caused by the bombing of the mills situated in the London Docks, the production at Ponders End was considerably increased. This was achieved by extending the working of the mill to seven days a week and 52 weeks a year for the duration of the war. Fortunately the mill did not suffer any serious damage from enemy action, although constant operation of the plant took its toll on the machinery.

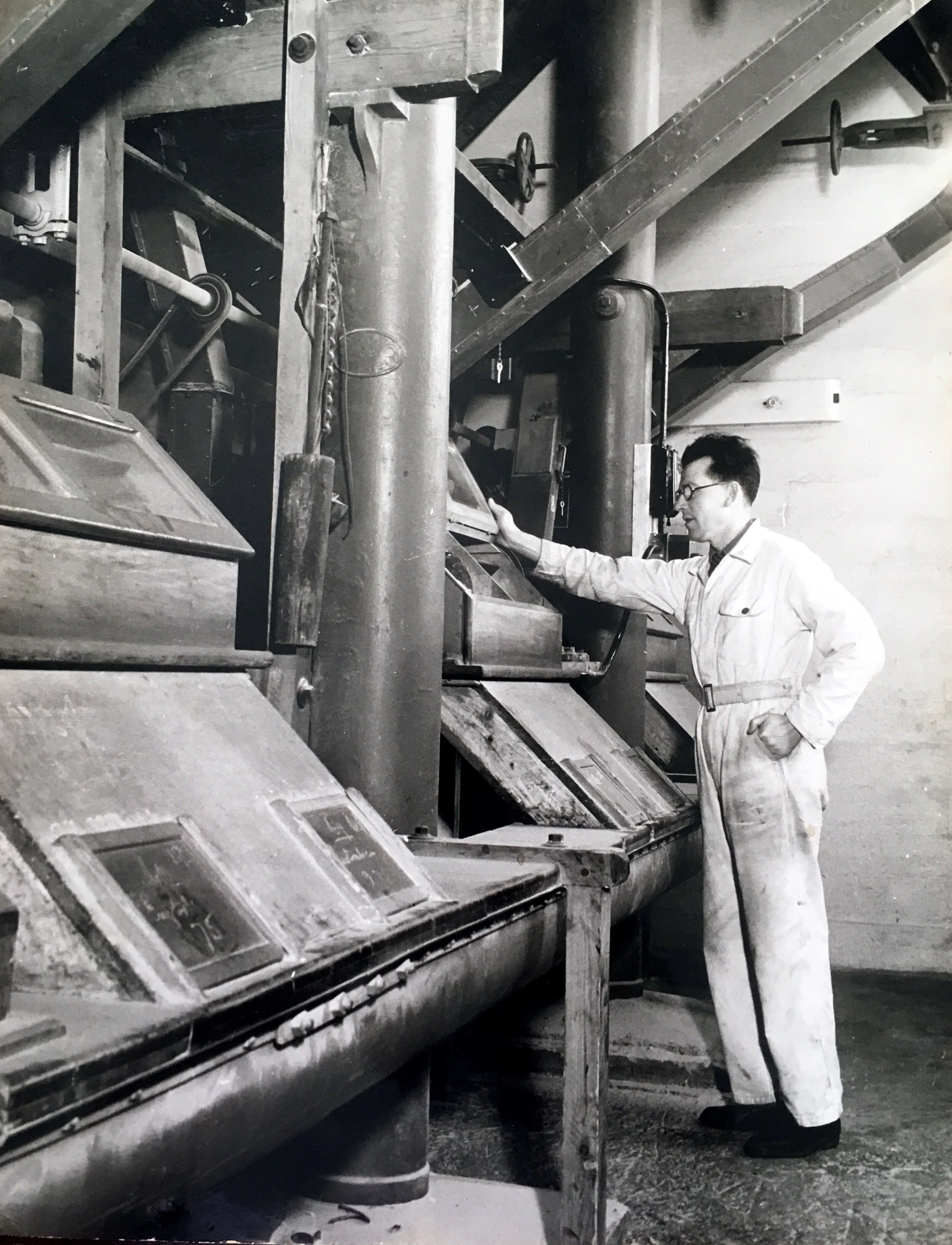

By the early 1950s, with the mill back in family control, a decision was taken to modernise and refurbish the plant and machinery. The specialist firm of Thomas Robinson of Rochdale was called in and by April that year, only 10 weeks after modernisation began, the mill recommenced production with a 50 per cent increase in capacity. Flour could now be processed at the rate of twelve 28016 sacks per hour.

Company expansion still continues towards the millennium and beyond with improvements in buildings and equipment and the introduction of silos for bulk storage of grain and flour. Modern methods of production call for changes to the way, in which flour is transported, so Wright's have invested in bulk road tankers. No doubt the 19th-century wagon driver would have found these new methods of storage and delivery impossible to imagine.

Not resting on their laurels, the directors of Wright's have responded to changing public tastes, by introducing a number of new product lines particularly aimed at today's busy consumer. Speciality flours and bread mixes, which can be made quickly and easily, now appear on several supermarket shelves and expansion into overseas markets is an ongoing feature of the business strategy.

Over the years many Lea Valley companies have come and gone, but Wright's Mill stands as a glowing example of determination and entrepreneurship, a symbol of the ability of a family business to adapt product and processes to the needs of a highly competitive and ever changing industrial world.

The example of progression from Wright's early Lea Valley roots and the company's successful expansion into the 20th century must surely act not only as encouragement to other firms wishing to set up in the region, but as a continuing reminder of how to adapt and prosper. Here are important lessons for us all to learn and perhaps the Wright model can supply some valuable clues for industry in general, pointing the way to future regeneration of the region.